On December 15, 2021, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve System made a significant shift in monetary policy in response to rising inflation. The Committee accelerated the reduction of its bond-buying program in order to tighten the money supply and projected three increases in the benchmark federal funds rate in 2022, followed by three more increases in 2023. Both steps were more aggressive than previous FOMC actions or projections.1

To understand how these steps might affect the U.S. economy, investors, and consumers, it may be helpful to take a closer look at the FOMC's tools and strategy.

The Fed's current plan is aimed at slowing inflation by returning to a more neutral monetary policy.

As the nation's central bank, the Federal Reserve operates under a dual mandate to promote price stability and maximum sustainable employment. This is a balancing act, because an economy without inflation is typically stagnant with a weak employment climate, while a booming economy with plenty of jobs is susceptible to high inflation.

The FOMC, which is responsible for setting monetary policy in line with the Fed's mandate, has established a 2% annual inflation target based on the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. The PCE index represents a broad range of spending on goods and services, and tends to run below the more widely publicized consumer price index (CPI). The Committee's policy is to allow PCE inflation to run moderately above 2% for some time in order to balance the periods when it runs below 2%.

PCE inflation was generally well below the Fed's 2% target from May 2012 to February 2021. But it has risen quickly since then, reaching 5.7% for the 12 months ending in November 2021 — the highest level since 1982. (By comparison, CPI inflation was 6.8%.)2,3

Fed officials, along with many other economists and policy makers, originally believed that inflation was "transitory" due to supply-chain issues related to opening the economy. But the persistence and level of inflation over the last few months led them to take corrective action. They still believe inflation will drop significantly in 2022 as supply-chain problems are resolved, and project a PCE inflation rate of 2.6% by the end of the year.1

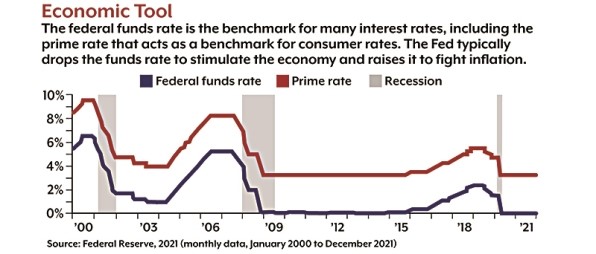

The FOMC uses two primary tools in its efforts to achieve the appropriate balance between employment and prices. The first is its power to set the federal funds rate, the interest rate that large banks use to lend each other money overnight in order to maintain required deposits with the Federal Reserve. This rate serves as a benchmark for many other rates, including the prime rate that commercial banks charge their best customers. The prime rate usually runs about 3% above the federal funds rate (see chart) and acts as a benchmark for rates on consumer loans such as credit cards and auto loans. The FOMC lowers the funds rate to stimulate the economy to create jobs and raises it to slow the economy to fight inflation.

The Fed's second tool is purchasing Treasury bonds to increase the money supply or allowing bonds to mature without repurchasing in order to decrease the supply. The FOMC purchases Treasuries through banks within the Federal Reserve System. Rather than using funds it holds on deposit, the Fed simply adds the appropriate amount to the bank's balance, essentially creating money out of air. This provides the bank with more money to lend to consumers, businesses, or the government (through purchasing more Treasuries).

When the economy shut down in March 2020 in response to the COVID pandemic, the FOMC took extraordinary stimulus measures to avoid a deep recession. The Committee dropped the federal funds rate to its rock-bottom range of 0% to 0.25% and began a bond-buying program that reached an unprecedented level of $75 billion per day in Treasury bonds. By June 2020, this was reduced to $80 billion per month and remained at that level until November 2021, when the FOMC decided to wind down the program at a rate that would have ended it by June 2022.4,1

The December decision accelerated the wind down, so the bond-buying program will end in March 2022, at which point the FOMC will likely consider raising the federal funds rate. Although it's not certain when an increase will occur, the December projection is that the rate will be in the 0.75% to 1.00% range by the end of 2022 and the 1.50% to 1.75% range by the end of 2023.1

The Fed's current plan is aimed at slowing inflation by returning to a more neutral monetary policy; this represents confidence that the economy is strong enough to grow without extreme stimulus. If these are the only actions required, the impact may be relatively mild. And the first rate increase will likely not occur until the spring.

Even so, rising interest rates make it more expensive for businesses and consumers to borrow, which could impact corporate earnings and consumer spending. And rates have an inverse relationship with bond prices. As interest rates rise, prices on existing bonds fall (and vice versa), because investors can buy new bonds paying higher interest.

On the other hand, higher rates on bonds, certificates of deposit (CDs), savings accounts, and other fixed-income vehicles could help investors, especially retirees, who rely on fixed-income investments. Brick-and-mortar banks typically react slowly to changes in the federal funds rate, but online banks may offer higher rates.5

As 2022 begins, inflation is a far greater concern than rising interest rates, and it remains to be seen whether the Fed's projected rate increases will be enough to tame prices. For now, it may be best not to overreact to the policy shift and maintain an investment portfolio appropriate for your long-term goals.

U.S. Treasury securities are guaranteed by the federal government as to the timely payment of principal and interest. The principal value of all bonds fluctuates with market conditions. Bonds not held to maturity could be worth more or less than the original amount paid. The FDIC insures CDs and bank savings accounts, which generally provide a fixed rate of return, up to $250,000 per depositor, per insured institution. Forecasts are based on current conditions, subject to change, and may not come to pass.

1 Federal Reserve, 2021

2 U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2021

3 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021

4 Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2021

5 Forbes Advisor, December 14, 2021

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES: Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc. does not provide investment, tax, legal, or retirement advice or recommendations. The information presented here is not specific to any individual's personal circumstances. To the extent that this material concerns tax matters, it is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, by a taxpayer for the purpose of avoiding penalties that may be imposed by law. Each taxpayer should seek independent advice from a tax professional based on his or her individual circumstances. These materials are provided for general information and educational purposes based upon publicly available information from sources believed to be reliable — we cannot assure the accuracy or completeness of these materials. The information in these materials may change at any time and without notice.