With news of the United States reaching the debt ceiling, and the threat of default dominating the headlines, it can be very confusing to differentiate fact from opinion. Add to that the political backdrop of the balance of power in Congress, and it oftentimes turns into a partisan debate. Here is a breakdown of what it all means, how we got here, why this even matters, as well as possible outcomes.

Key Terms

The debt ceiling is the legal limit on the amount of money the US government can borrow to meet its existing obligations. Put simply, it is the maximum amount of money the US government can borrow to pay its bills. These “bills” include direct spending (debt payments and entitlements such as Social Security and Medicare) and discretionary spending (items that have already been approved, including annual appropriations to specific federal government departments, agencies or programs). On December 29, 2022 President Biden signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 outlining $1.7 trillion in federal spending for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2023.

The federal budget is comprised of revenues (money coming in from tax receipts) and spending (money going out). A surplus occurs when revenues exceed expenses in a given year. Conversely, a deficit occurs when expenses exceed revenues in a given year, resulting in a shortfall or loss. While a deficit is not uncommon, and at times government may intentionally incur a deficit to help run programs and projects, it is unsustainable over long periods of time.

Evolution of the Debt Ceiling

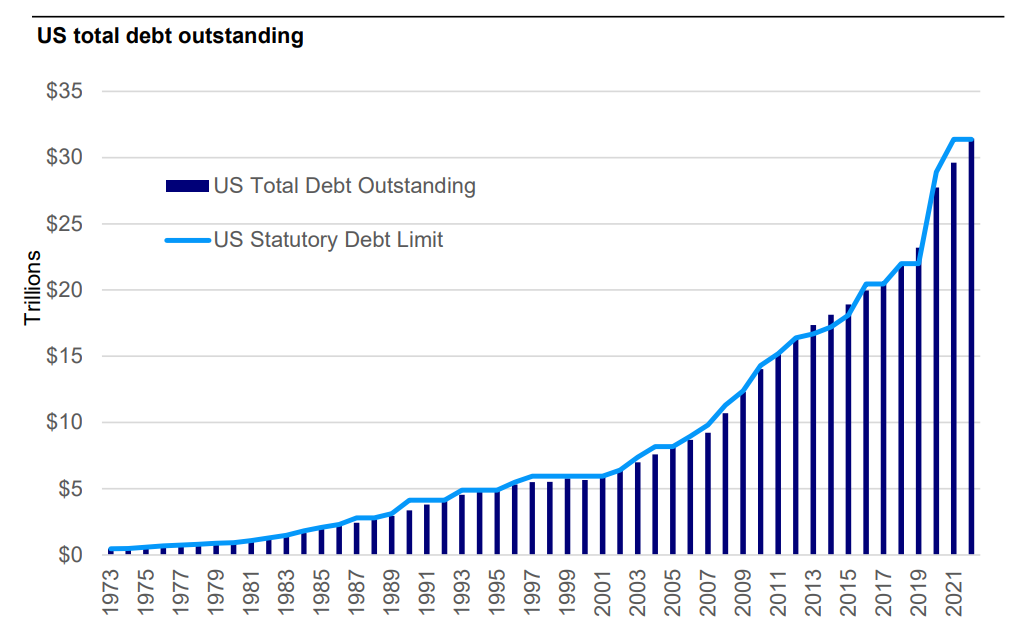

Throughout history, the US government has borrowed money by selling US Treasury bills, notes, and bonds to cover any shortfall. The accumulation of this borrowing along with associated interest owed is the national debt. Up until World War I, Congress maintained tight control over federal borrowing and imposed limits on each debt instrument. The Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917 broadened the scope of government borrowing to meet expenditures originally authorized for national security and defense to include other public purposes authorized by law. In 1939, Congress imposed an aggregate debt limit of $45 billion. However, leeway in issuing new debt, coupled with the imposed debt limit has not kept borrowing static, nor has it curbed spending. Congress has acted 78 times since 1960 to raise, temporarily extend, or revise the definition of the debt limit, under both Democratic and Republican presidents. The US has experienced a fiscal year end budget surplus five times in the last 50 years, most recently in 2001 at the end of Clinton’s presidency. Since then, the US has been running deficits. Put another way, the government has spent more than it took in from taxes or other revenues in 45 of the last 50 years, regardless of any increase in the debt ceiling. On January 19, 2023 the US government reached the current debt limit of $31.4 trillion.

Source: US Treasury, 12/31/22

Ideally, for government to have a balanced budget, REVENUES=SPENDING. When this is not the case and there is a deficit, REVENUES+BORROWING=SPENDING. Historically Congress has raised the debt ceiling, allowing additional borrowing to cover the shortfall. The only other options to maintain the balance would be to increase revenues (raise taxes) or reduce spending (restrict programs and/or reform entitlements). If there are no changes to the equation, inevitably there would be a default on the debt, meaning the government would not be able to pay its existing obligations to holders of US Treasury debt.

Current Situation

The US has never defaulted on its debt. The last major faceoff to the debt ceiling was in 2011 when a newly divided Congress used the debt ceiling as a bargaining tool in the ongoing political debate about government spending. The debt ceiling was ultimately lifted, but not until the day the Treasury thought it might run out of cash. This led to S&P downgrading the US long-term credit rating from AAA to AA+, for the first time in history! The debt limit was tested again in 2013, but to a lesser extent than 2011. In both instances, there was market volatility throughout negotiations. This resulted in a corresponding selloff in equities and a flight to quality, a financial market occurrence where investors seek less risk in exchange for lower returns.

For now, the Treasury is implementing “extraordinary measures” to keep spending within the limit. Basically, the Treasury is moving money around and prioritizing payments to bide time. An actual default could create a panic, since any perceived threat that Treasury investments are no longer safe could have profound financial and liquidity implications. It could also affect global financial markets, especially since other countries rely on the economic and political stability of US debt instruments.

There is dissention in Congress around lifting the borrowing cap. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and Republicans who have narrow control in the House pose that raising the debt limit be accompanied by spending cuts. Meanwhile, President Biden and Democrats who control the Senate counter that they will not negotiate or offer concessions.

Looking Ahead

Whether Congress decides to raise the debt ceiling, suspend the limit, make spending cuts, or ultimately default remains to be seen. Increasing the debt ceiling is not definite, and there is opposition in Congress. The Treasury’s “extraordinary measures” will only last so long. Moreover, even if the debt ceiling is raised and the US government avoids default, the debate over federal taxes and government spending will continue. Uncertainty surrounding an increase of the debt ceiling may heighten market volatility which our disciplined approach to investing and asset allocation is designed to mitigate. Our portfolios are created not only to participate in market upswings but also to lessen downside risk. Headlines can be worrisome, but you can rest assured that our portfolios are positioned to protect you throughout the changing economic and political landscape, and we encourage you to stay the course.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES: Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc. does not provide investment, tax, legal, or retirement advice or recommendations. The information presented here is not specific to any individual's personal circumstances. To the extent that this material concerns tax matters, it is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, by a taxpayer for the purpose of avoiding penalties that may be imposed by law. Each taxpayer should seek independent advice from a tax professional based on his or her individual circumstances. These materials are provided for general information and educational purposes based upon publicly available information from sources believed to be reliable — we cannot assure the accuracy or completeness of these materials. The information in these materials may change at any time and without notice.